The Federal Reserve wants you to believe they're winning the war on inflation. They cut rates in September, they're cutting again this week, and Fed Chair Jerome Powell keeps reassuring us that everything is under control. The official line? Inflation is trending back to the magical 2% target, the labor market needs support, and monetary policy is working exactly as intended.

Here's what they're not telling you: inflation is stuck at 3%, a full 50% above target. Trump's tariffs are embedding themselves into the price structure of the entire economy. The Fed's balance sheet is still bloated at $6.6 trillion even after years of "quantitative tightening." And now they're about to hit pause on the one contractionary policy they actually implemented.

The uncomfortable truth? The Fed has already lost this fight. They just haven't admitted it yet.

The Inflation Nobody Wants to Talk About

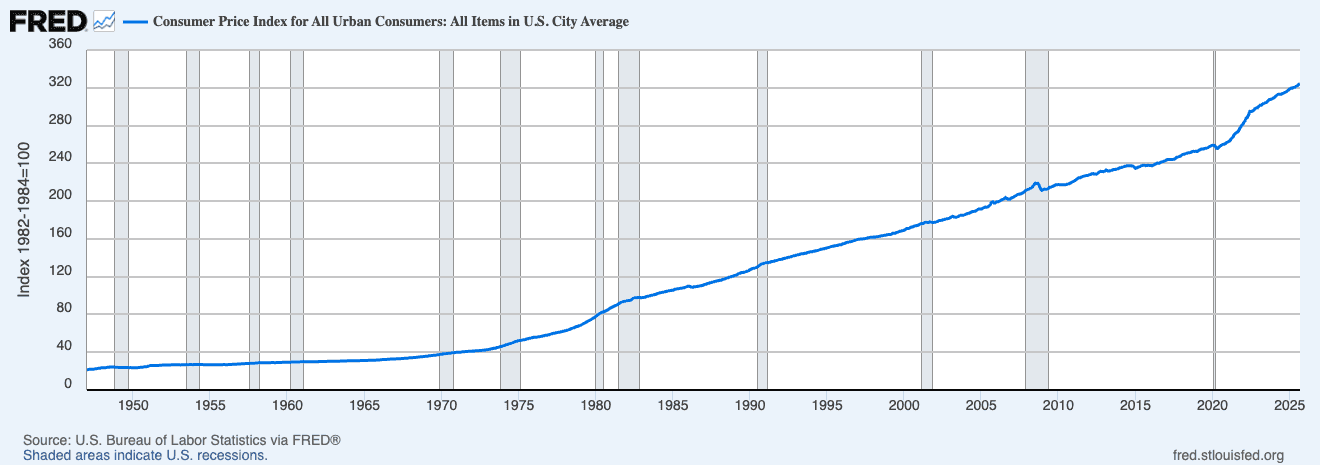

Let's start with the numbers everyone's ignoring. September's CPI came in at 3.0% year-over-year, slightly below the 3.1% economists expected. Wall Street celebrated. Powell nodded approvingly. Mission accomplished, right?

Wrong. That 3% figure represents inflation that's been "sticky around this 3% level" for months, as Wells Fargo's chief economist noted. Core inflation? Also 3%. The Fed's preferred PCE measure? You guessed it—stubbornly elevated and showing no real inclination to cooperate with the 2% fantasy.

Here's what makes this particularly insidious: we're nine months past the initial tariff announcements, and only 35% of tariff costs have been passed through to consumers so far, according to St. Louis Fed research. The other 65%? It's coming. Companies have been eating the costs, depleting pre-tariff inventories, and waiting for the political theater to settle. That bill is about to come due.

The Budget Lab at Yale estimates that current tariff policies will cost the average household $1,800 in 2025. And with the effective tariff rate now at 18.6%—the highest since 1933—we're looking at embedded inflation that monetary policy simply can't fix. You can't interest-rate your way out of a supply-side shock.

The Rate Cut Trap

So what does the Fed do when faced with inflation that won't cooperate? They cut rates anyway. The FOMC cut by 25 basis points in September, and markets are pricing in near-certainty for another quarter-point cut this week, followed by likely cuts in December.

This is monetary policy on autopilot, driven more by political pressure and labor market anxieties than actual inflation realities. Trump has been relentless, calling for rate cuts totaling as much as 3 percentage points. He even tried to fire Fed Governor Lisa Cook (she sued). His White House appointee to the Fed board, Stephen Miran, dissented at the September meeting, pushing for a 50-basis-point cut instead of 25.

The Fed's independence? It's a nice bedtime story we tell ourselves.

Here's the problem: cutting rates while inflation remains elevated isn't stimulus—it's surrender. It's the Fed admitting they can't hit their inflation target without causing unacceptable pain in the labor market. Powell has essentially said as much, noting the Fed faces a "difficult situation of balancing those two things" between inflation and employment.

Translation: We're going to tolerate 3% inflation because we're terrified of a recession.

The Balance Sheet Charade

Now let's talk about the elephant in the room that's somehow both enormous and invisible: the Fed's balance sheet.

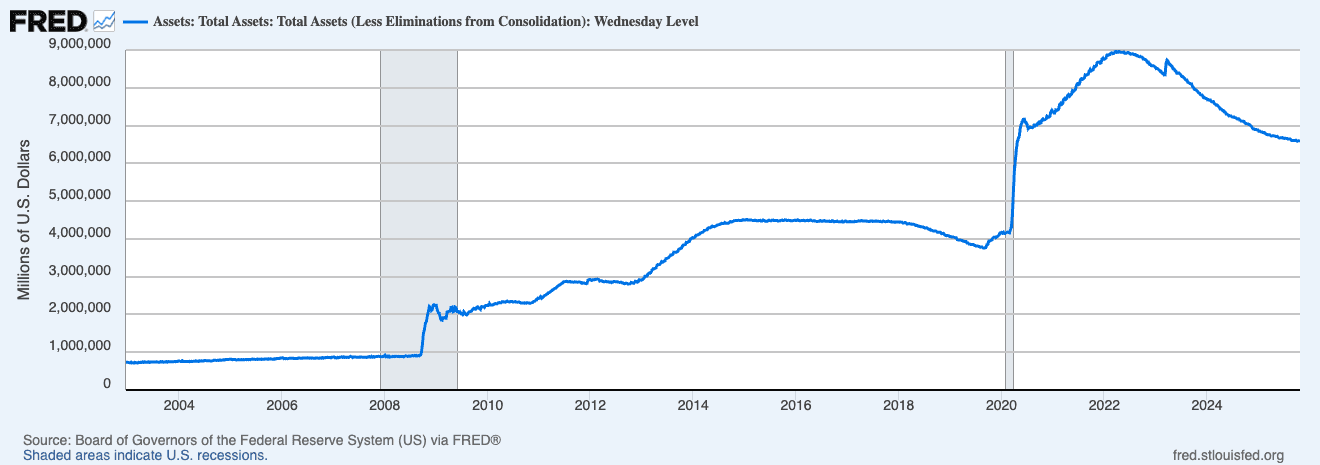

Since June 2022, the Fed has been running quantitative tightening—allowing securities to roll off the balance sheet without reinvestment. They've shed over $2 trillion from the peak of $9 trillion, which sounds impressive until you realize they're still sitting at $6.6 trillion. For context, that's roughly where they were in mid-2020, when we were in full pandemic-panic mode.

And now? They're about to stop. Powell signaled in October that "we may approach that point in coming months" where QT ends. The reason? "Some signs have begun to emerge that liquidity conditions are gradually tightening," with repo rates spiking as banks hoard reserves.

Let's be clear about what this means: The Fed tried to normalize monetary policy, made it about 25% of the way there, and now they're tapping out. They can't even drain liquidity back to pre-crisis levels without threatening market stability.

This isn't a temporary balance sheet. This is the new baseline. The Fed has painted itself into a corner where they need "ample reserves" to maintain control over interest rates—which means a permanently bloated balance sheet and a permanently higher monetary base than historical norms would suggest is appropriate.

The M2 Money Supply Red Flag

Speaking of the monetary base, let's talk about M2 money supply—the measure that includes cash, checking deposits, savings accounts, and money market funds. You know, the stuff that actually sloshes around the economy and influences prices.

M2 hit $22.1 trillion in July 2025, a record high, with year-over-year growth at 4.5% in April—the highest rate since July 2022.

Remember 2022? That's when inflation hit 9.1%, the highest in four decades. And now money supply growth is accelerating again, right as the Fed is cutting rates and preparing to stop balance sheet runoff. It's like watching someone pour gasoline on a fire while insisting they're putting it out.

The monetarist argument here is straightforward: more money chasing roughly the same amount of goods equals higher prices. The Fed can spin whatever narrative they want about "transitory" tariff impacts or "temporary" supply shocks, but when you're expanding the money supply while cutting rates and maintaining a $6.6 trillion balance sheet, you're not fighting inflation—you're accommodating it.

The Tariff Time Bomb

Let's circle back to the tariff situation, because this is where the Fed's loss of control becomes most obvious. Goldman Sachs estimates that businesses could eventually pass on as much as 55% of tariff costs to consumers. Currently, we're at 35%. Do the math.

The Atlanta Fed's recent survey found that businesses—both those directly exposed to tariffs and those who aren't—expect to raise prices this year. By mid-May, firms anticipated price increases of 3.5%, up from 2.5% at the end of 2024.

Here's what makes this particularly pernicious: these aren't one-time price level adjustments. They're embedded cost increases that work their way through supply chains, contracts, and wage negotiations. When furniture prices jump, car parts get more expensive, and electronics cost more, those increases create a new baseline that subsequent inflation builds upon.

The Fed can raise rates all they want (except they're cutting them), but monetary policy doesn't fix tariffs. It can't unwind supply chain fragmentation or recreate global trade networks that took decades to build. Powell has been explicit about this: "Many of the issues—such as high regulatory costs and a persistent housing shortage—can't be solved by monetary policy alone."

The Labor Market Excuse

Now we get to the Fed's favorite justification for cutting rates: the weakening labor market. Only 73,000 jobs were added in July, and revisions showed 258,000 fewer jobs in previous months than initially reported. The unemployment rate ticked up. Fed officials started sweating.

Here's what's convenient about focusing on employment: it gives them political cover to cut rates even while inflation remains elevated. Powell can point to the Fed's dual mandate—price stability and maximum employment—and argue they're balancing both concerns.

But look closer at what's actually happening. We're not seeing mass layoffs (federal job cuts notwithstanding). We're seeing hiring slowdowns, particularly for new graduates and job switchers. This is exactly what you'd expect in an economy dealing with uncertainty around tariffs, regulatory changes, and elevated costs. It's adjustment, not collapse.

The Fed is using labor market softness as an excuse to ease policy precisely when they should be maintaining restrictive conditions to finally break the back of inflation. They're choosing the politically palatable path of supporting employment over the harder work of ensuring actual price stability.

The Government Shutdown Wild Card

Adding another layer of absurdity to this situation: the federal government has been shut down since October, and most economic data releases have been suspended. The Fed is essentially flying blind, making policy decisions based on partial information and private-sector estimates.

The September CPI report? Only released because Social Security needed it to calculate cost-of-living adjustments. The jobs report? Missing in action. GDP data? Unavailable. The Fed is cutting rates without full visibility into what's actually happening in the economy.

Powell acknowledged this challenge, noting it's "hard to make policy to achieve two goals when you're not getting data about at least one of them." But rather than waiting for clarity, the Fed is plowing ahead with rate cuts, apparently confident that easing is appropriate regardless of what the missing data might show.

This is policy by vibes, not data. And when the data does eventually show up, don't be surprised if it reveals that inflation never really came down the way the Fed claimed.

What This Means for Your Money

The practical implications of the Fed's loss of control are straightforward:

Higher sustained inflation: That 3% floor isn't going anywhere. Expect inflation to remain elevated indefinitely, with potential spikes as tariff pass-through accelerates.

Continued rate cuts despite inflation: The Fed will keep easing because they're more concerned about recession optics than price stability. Mortgage rates might fall slightly to the low-6% range, but don't expect the 3-4% rates of the pre-pandemic era.

Dollar debasement: With M2 growing at 4.5% and the Fed maintaining a massive balance sheet while cutting rates, your dollars are losing purchasing power faster than official inflation statistics suggest.

Asset price distortion: Markets will continue to be supported by loose monetary policy despite economic fundamentals that would typically warrant tighter conditions. This creates fragility and increases the risk of sharp corrections when reality eventually intrudes.

Real negative interest rates: With inflation at 3% and the Fed cutting toward 3.5-3.75% by year-end, real rates are barely positive or negative depending on which inflation measure you use. This punishes savers and rewards debtors—classic financial repression.

The Endgame

The Fed has trapped itself. They can't raise rates because the labor market is softening and political pressure is intense. They can't keep running QT because liquidity conditions are tightening and markets are getting twitchy. They can't ignore tariff-driven inflation because it's not going away.

So they're choosing the path of least resistance: cutting rates, stopping balance sheet runoff, and hoping that somehow inflation magically declines to 2% despite all evidence suggesting it won't.

This isn't a masterclass in central banking. It's surrender dressed up as "data-dependent" policy.

The uncomfortable reality is that the Fed's 2% inflation target is dead. It died somewhere between the tariff wars, the political pressure campaign, and the realization that returning to truly restrictive monetary policy would require more pain than our political system is willing to tolerate.

What we're left with is a Fed that maintains the fiction of inflation-fighting credibility while actually accommodating 3%+ inflation indefinitely. They'll dress it up in technical language about "average inflation targeting" and "flexible frameworks," but the substance is the same: they've lost control and they're not getting it back.

The only question now is how long they can keep pretending otherwise—and what breaks first when markets figure out the game.

NEVER MISS A THING!

Subscribe and get freshly baked articles. Join the community!

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.

Related post

February 24, 2026

February 19, 2026

February 12, 2026