Remember 2008? The repo market seizure that brought the global financial system to its knees? The "shadow banking" entities that melted down and nearly took traditional banks with them? We were told regulators learned their lesson. New rules were written. Safeguards were implemented. The system was fixed.

They lied.

The shadow banking system—that sprawling network of lightly-regulated or completely unregulated financial intermediaries conducting bank-like activities without safety nets—has not only recovered from 2008. It's exploded to an estimated $63 trillion globally, representing 78% of global GDP. In the U.S. alone, banks have now lent over $1 trillion to shadow banking entities, up 20% year-over-year as of March 2025. And projections suggest the sector will hit $148.5 trillion by 2032.

Here's what nobody wants to admit: we're staring at a financial system that's even more fragile than the one that collapsed in 2008, except now it's significantly larger, more interconnected, and operating in darker corners with less visibility than ever before.

What We're Actually Talking About

Let's define terms, because "shadow banking" covers a staggering array of entities that most people have never heard of but are intimately connected to their financial lives.

The shadow banking system encompasses any credit intermediation happening outside traditional regulated banks—entities that perform bank-like functions (maturity transformation, credit transformation, liquidity provision) without access to central bank funding or deposit insurance. We're talking about:

Private credit funds lending to mid-market companies

Money market funds that broke the buck in 2008 and nearly did again in 2020

Hedge funds leveraging up repo market positions

Asset-backed commercial paper conduits

Business development companies (BDCs)

Mortgage companies and non-bank lenders

Buy-now-pay-later companies

Structured investment vehicles

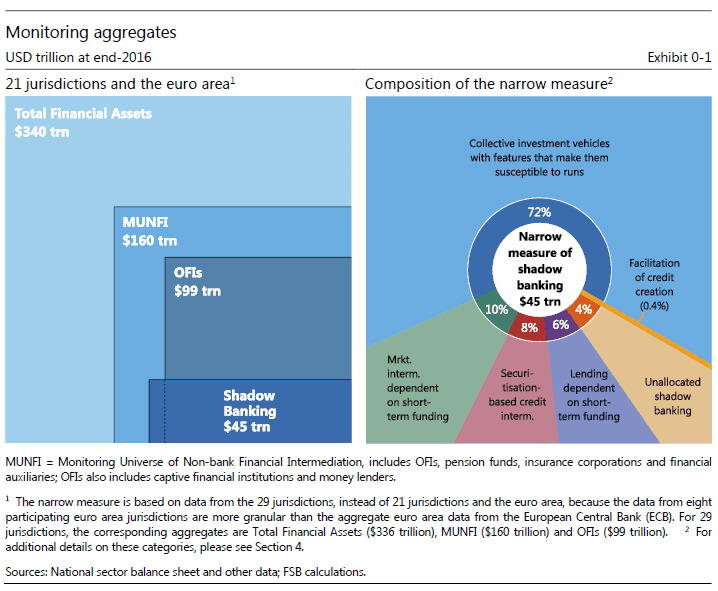

The Financial Stability Board's monitoring framework tracks 29 jurisdictions representing over 80% of global GDP, and even they admit their numbers are conservative. The true size is probably larger—much larger—because shadow banking by definition operates in the shadows, and entities structured to avoid regulatory scrutiny don't exactly advertise their systemic importance.

The Private Credit Explosion

Nowhere is shadow banking's growth more dramatic than in private credit. This sector—where specialized non-bank entities lend to corporate borrowers outside public markets—has mushroomed from virtually nothing to $1.7 trillion in assets under management as of March 2025, with projections hitting $2.1 trillion globally.

The pitch sounds reasonable: traditional banks retreated from middle-market lending after post-2008 regulations made it capital-intensive and unprofitable. Private credit funds stepped in to fill the gap, offering borrowers speed, flexibility, and certainty of execution. Institutional investors loved the higher returns and "stable" income streams. Win-win, right?

Wrong. Here's what's actually happening:

The borrowers are riskier. Companies tapping private credit are smaller and carry more debt than their leveraged-loan or high-yield bond counterparts. Interest coverage is weaker (2.1x versus 3.9x for public markets), leverage is higher (5.6x versus 4.6x), and EBITDA margins are slimmer (14.9% versus 16.4%). These aren't companies that traditional banks rejected for fun—they were rejected because the credit risk didn't pencil out.

The valuations are fiction. Unlike public markets where prices update continuously, private credit valuations happen quarterly using subjective models. The IMF notes that despite having lower credit quality, private credit assets show smaller markdowns during stress than leveraged loans that trade in liquid markets. Translation: fund managers are marking their positions to fantasy, not reality, because they can get away with it in illiquid markets.

The leverage is hidden. While individual funds claim modest leverage, there are multiple layers of leverage buried in the structure: the portfolio company has leverage, the private equity sponsor typically uses leverage at the holding company level, and the BDCs or funds themselves often borrow from banks. Boston Fed research found banks have extended around $95 billion in loans to private credit lenders—and that's just what's visible. The real number is likely higher.

Competition is destroying standards. With $1.7 trillion raised in just five years, managers are desperate to deploy capital. The predictable result? Looser underwriting standards, weaker covenants, and spread compression that doesn't adequately compensate for risk. When everyone's chasing the same deals, credit discipline goes out the window.

The Repo Market Powder Keg

If private credit is the slow-motion train wreck, the repo market is the detonator that could blow the whole thing up instantly.

The repo (repurchase agreement) market is the circulatory system of modern finance—a $4+ trillion overnight lending market where financial institutions borrow cash using securities as collateral. It's invisible until it breaks, and it's showing signs of stress.

In mid-September 2025, the Fed's Standing Repo Facility was tapped for $18.5 billion—the largest draw since its inception. SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate) spiked to 4.42%, with related benchmarks climbing in tandem. By October 15, another $6.75 billion operation signaled ongoing funding stress.

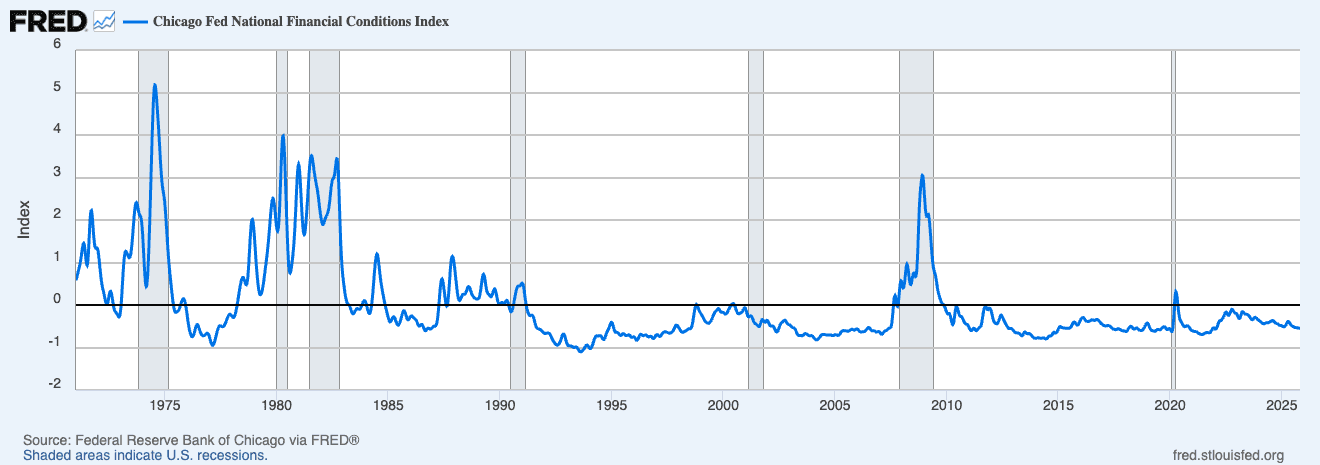

Sound familiar? It should. In September 2019, the repo market seized up when overnight rates suddenly spiked from 2% to over 8% in a single day. The Fed had to inject up to $100 billion daily to prevent a complete meltdown. The official explanation: a temporary imbalance from tax payments and Treasury settlement. The reality: the system was already operating on the edge of failure, and a relatively minor drain exposed the fragility.

Now we're back at that edge. Bank reserves have fallen below $3 trillion—the threshold many Fed officials consider the line between "ample" and "strained" reserves. The Fed's reverse repo facility, which absorbed excess liquidity and provided a safety valve, has essentially emptied out. The buffer that prevented 2019 from becoming 2008 is gone.

Why does this matter? Because shadow banks—particularly hedge funds—are massively dependent on repo funding for their leveraged positions. When repo markets get stressed, these entities face margin calls and forced liquidations, which creates a doom loop: selling assets depresses prices, which triggers more margin calls, which forces more selling.

And unlike 2019, we now have collateral re-use adding another layer of fragility. Securities posted as collateral get rehypothecated multiple times throughout the system, meaning the same Treasury bond might be supporting several different transactions simultaneously. When everyone tries to retrieve their collateral at once—well, that's when you discover there aren't enough bonds to go around.

The Bank-Shadow Bank Doom Loop

Here's where it gets truly terrifying: the lines between regulated banks and shadow banks have completely blurred.

Traditional banks are now deeply interconnected with shadow banking entities. Fitch Ratings found lending from banks to shadow banks was up 20% year-over-year as of March 2025, while commercial lending grew only 1.5%. Banks are essentially outsourcing their riskiest lending to unregulated entities, then lending to those entities so they can make the loans banks don't want on their own balance sheets.

Read that again: banks are regulatory-arbitraging themselves by funding shadow banks to do what they're not supposed to do.

The New York Fed's research on private credit acknowledges this dynamic but downplays the risk, noting that bank loans to private credit funds are "typically secured and among those funds' most senior liabilities." Sure. Until the default correlation across private credit portfolios turns out to be higher than modeled—meaning more borrowers default simultaneously than anticipated. Then those "secured" loans take losses too.

We've seen this movie before. In 2008, banks thought they were protected because they'd offloaded risk to special purpose vehicles and structured investment vehicles. Turns out when the assets blow up, the losses come back to the originating banks through explicit commitments, implicit reputational risk, and the general contagion that happens when your counterparties all fail at once.

The difference now? The scale is bigger, the interconnections are denser, and the opacity is deeper.

The Regulatory Blindness

Regulators can't control what they can't see, and shadow banking operates specifically to evade oversight.

The Fed proposed rules in 2024 to collect more comprehensive data on banks' exposure to shadow banks, but that's like asking for better visibility after you've already driven into the fog at highway speed. The European Central Bank has been warning about shadow banking risks since 2021, achieving precisely nothing in terms of actual constraint.

Here's the problem: shadow banking grows because of regulation, not despite it. Every new rule for traditional banks creates an incentive for activities to migrate to less-regulated entities. Post-2008 capital requirements forced banks out of middle-market lending? Private credit filled the void. Money market fund reforms made prime funds less attractive? The activity shifted to offshore vehicles and unregulated alternatives.

It's regulatory whack-a-mole, except the moles are $63 trillion in systemic risk, and regulators are swinging in slow motion.

Meanwhile, China's shadow banking sector—which peaked in 2017 at astronomical levels—has supposedly been reined in through aggressive regulatory crackdowns. But as everyone who follows China knows, when Beijing announces they've solved a problem, it usually just means they've moved the problem somewhere less visible. Trust sector property exposure dropped from $2.9 trillion to $1 trillion, they say. Where did the other $1.9 trillion go? Good question. Nobody really knows.

The Liquidity Crisis Nobody's Admitting

All of this—private credit, repo stress, bank-shadow bank interconnections—exists against the backdrop of a Fed that just stopped quantitative tightening because they couldn't drain liquidity without threatening financial stability.

Think about what that means. The Fed raised rates aggressively to fight inflation. They tried to normalize their balance sheet by letting securities roll off. They made it about 25% of the way to pre-crisis conditions and had to stop because the system couldn't handle it. Bank reserves are already strained at $3 trillion—still double pre-crisis levels—and we're seeing funding stress.

Now overlay shadow banking on top of this fragile liquidity picture. Shadow banks don't have access to the Fed's discount window. They can't borrow from the central bank in a crisis. They rely on continuous funding from money markets, repo markets, and bank credit lines. When those funding sources dry up—and they will, because that's what happens in crises—shadow banks face a stark choice: forced asset sales or default.

Either choice amplifies the crisis. Asset sales depress prices and spread contagion to anyone holding similar assets. Defaults hit the banks and institutions that funded them, potentially triggering the next round of failures.

A former Fed advisor recently declared that "a systemic liquidity crisis is already unfolding," pointing to repo market stress and the unexpected activation of the Standing Repo Facility as concrete signals. The implication: the Fed may be forced to abandon inflation-fighting not because they've won, but because the financial system is fracturing.

The Coming Reckoning

So where does this end? Probably not well.

The optimistic case is that private credit losses remain manageable, funding markets stay relatively stable, and regulators figure out how to contain shadow banking risks before they metastasize into a systemic crisis. This requires no major economic downturn, no geopolitical shocks, no unexpected defaults that trigger contagion, and regulators suddenly becoming competent at overseeing a system designed to evade oversight.

Put me down as skeptical.

The realistic case looks like this: tariff-driven inflation and slowing growth stress corporate borrowers. Private credit default rates rise above the current 2.4%, and those quarterly mark-to-model valuations start getting uncomfortable. Some funds gate redemptions or suspend distributions. Banks that lent to private credit funds face questions about their exposure. Funding markets tighten.

Simultaneously, repo market stress intensifies as the Fed's balance sheet runoff has removed liquidity buffers. Some highly-leveraged hedge fund or family office blows up spectacularly, triggering a scramble for collateral. Rates spike. The Standing Repo Facility gets maxed out. The Fed is forced to inject emergency liquidity while inflation is still above target—the worst possible optics.

Markets realize the shadow banking system isn't actually safer than traditional banks—it's just less transparent. Risk premiums gap wider. Credit spreads blow out. The interconnections between banks and shadow banks become painfully obvious as losses ricochet through the system.

Politicians demand to know why nobody warned them about shadow banking risks. (Spoiler: people did, they just didn't listen.) Regulators propose sweeping new reforms. Shadow bankers threaten to move offshore if regulations get too burdensome. The cycle continues.

The catastrophic case—the one that keeps former regulators up at night—is 2008 redux but with more leverage, less transparency, and a Fed that has exhausted much of its ammunition fighting the last war. Multiple shadow banking entities fail simultaneously, banks take massive losses on their exposure, repo markets seize, and the whole house of cards comes down.

This time, the public's appetite for bailouts is approximately zero. Politicians who greenlight trillion-dollar rescues of opaque financial entities will be voted out of office. But the alternative—letting systemically important institutions fail—risks a depression.

Rock, meet hard place.

What This Means for You

If you're waiting for regulators or policymakers to prevent this crisis, stop. They're not going to. They've had 17 years since 2008 to rein in shadow banking and they've accomplished the opposite.

The shadow banking system is now larger than it was pre-crisis, more interconnected with traditional finance, and operating with even less transparency. Private credit firms are making increasingly risky loans to increasingly risky borrowers using increasingly optimistic valuations. Repo markets are showing stress signals. The Fed's liquidity buffers are depleted. Banks are neck-deep in shadow banking exposure despite everyone claiming to have learned their lesson.

The people running the system aren't stupid—they know this is fragile. They're just hoping the music doesn't stop on their watch. When it does stop, the scramble for chairs will be spectacular to watch and catastrophic to experience.

The only question is timing. Will it be a gradual unwind as private credit losses mount? A sudden liquidity crisis in funding markets? A cascade of failures triggered by some external shock we're not even thinking about yet?

Nobody knows. But the setup is there, the vulnerabilities are growing, and the longer shadow banking continues its explosive growth without meaningful oversight, the worse the eventual reckoning will be.

So buckle up. The shadow banking system that nearly destroyed the economy in 2008 is back, bigger than ever, and operating in even darker corners. When it blows up—and it will—don't say you weren't warned.

NEVER MISS A THING!

Subscribe and get freshly baked articles. Join the community!

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.

Related post

February 24, 2026

February 19, 2026

February 12, 2026